Submarine

Past, Present, and Future |

|

|

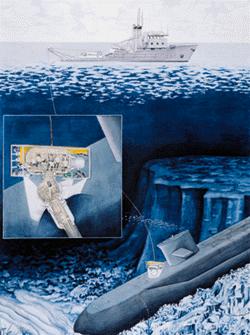

Past: For almost 100 years now, U. S. submarines have accomplished a wide variety of missions while establishing an excellent safety record. From the intelligence-gathering missions and SSBN patrols of the Cold War, to the launching of Tomahawk land-attack cruise missiles during the 1991 Gulf War, the Submarine Force has operated in all oceans under a broad range of environmental and tactical conditions. Submarines have always had a strong commitment to safety, which is reflected in their construction, emphasis on maintenance, training, and the sense of personal responsibility ingrained in every member of the ship’s crew. Nonetheless, the possibility still exists that a submarine may experience a casualty that requires outside assistance and the rescue of personnel. Motivated by lessons learned from the loss of the USS Thresher (SSN-593) in 1963, the Deep Submergence Rescue (DSRV) program was designed to fill the need for a system that could respond rapidly to similar emergencies. DSRV-1, Mystic, and DSRV-2, Avalon, were placed in “Service Special” in 1971 and 1972, respectively. They remain in full service today, providing both the United States and its allies a worldwide, quick-response submarine rescue capability unmatched by any other nation. The DSRVs have served for over 27 years, and thanks to improvements in reliability and the success of several cost-reduction programs, they will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. Present: Today, the crew of the Navy’s DSRVs and the officers and enlisted personnel of the Submarine Rescue Unit live with the realization that they may be called upon at any moment to respond to situations where lives are at stake. One of the Navy’s two Mystic-class DSRVs is kept in readiness at all times to respond immediately to potential submarine casualties, with the objective of arriving on scene within 72 hours of a mishap. In standby status, the San Diego-based units are prepared to load more than 200,000 pounds of equipment, including a 40-ton DSRV, onto a C-5B Galaxy aircraft and depart on four hours’ notice for any of 90 qualified rescue ports around the world. To maintain their “Rescue Ready” status, they exercise continually using both underway and in-port training to hone their skills in submarine rescue techniques, cargo handling, seamanship, contingency planning, and rapid deployment. All maintenance and training are planned around a rigid response time requirement, and as a result, since 1977 there has always been a DSRV ready to react to any potential submarine mishap. The crew of DSRV-2 Avalon convincingly demonstrated their readiness and versatility during the most recent NATO SORBET ROYAL exercise in 1996. The DSRV was launched from the after deck of the USS Sand Lance (SSN-660) and successfully demonstrated the ability to locate a simulated disabled submarine (DISSUB) on the bottom of a Norwegian fjord and transfer rescued personnel to a mother submarine. During a period of five days, Avalon and its crew successfully exercised their rescue procedures on simulated DISSUBs representing four different classes of NATO submarines, and proved that the U. S. submarine rescue system is ready today to do its job. Future: The likelihood of continuing budget reductions and the opportunities offered by advanced technology have spurred development of new concepts for a next-generation submarine rescue system. Alternatives to the existing approach are under evaluation with the goal of simplifying the existing DSRV support infrastructure and providing a submarine rescue capability with reduced life-cycle cost. The present DSRV support program, designed and implemented to accommodate the high submarine operating tempos of the Cold War era, is costly by today’s budget standards and subject to stringent certification requirements. Rescue systems that operate from surface ships of opportunity and deploy a simpler remotely operated vehicle with only two life support technicians are under development. This portable, modular system would be transported to the seaport nearest the rescue area and deployed on a surface ship pre-positioned there by rescue authorities. Once on scene, rescue personnel would launch the vehicle from the surface, mate it with the disabled submarine, and transport the crew to safety. The most challenging new requirement for the next-generation system is providing a capability to treat or safely transport personnel who have been exposed to hyperbaric (high-pressure) conditions while awaiting rescue. The ability to mount pressurized rescue operations has been lacking in the current DSRV system since the decommissioning of the two Pigeon (ASR-21)-class submarine rescue ships in 1995. To satisfy this need, the next-generation submarine rescue system will likely include integral surface decompression chambers. Also, biomedical research into hyperbaric phenomena and resulting new decompression techniques are allowing this shortfall to be addressed in the interim. A pending modification to the DSRVs will provide a stand-alone capability to decompress rescued crewman from up to five atmospheres before transferring them to the mother submarine. Overall, transitioning submarine rescue to this new system will not only provide a more flexible and capable submarine rescue system, but will also save the Submarine Force millions of dollars per year. |

||