by John Morgan, Captain U.S.

Navy

Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) remains the

linchpin of sea control. With forward presence and

expeditionary warfare rising to the top of Navy

priorities under the “New World Order,”

potential threats to our control of the intervening seas

are increasingly unacceptable. And since the

submarine threat is among the gravest of these, effective

ASW capabilities will be the sine qua non for our success

in future crises and conflicts. This is no less true now

than it was during the Cold War.

Despite the advance of technology, ASW

remains a complex challenge with neither simple nor

elegant solutions. Since the end of the Cold War and the

subsequent decline in defense budgets, however, that

challenge has become more severe. And yet, there are both

promising technical and operational developments and a

growing shift in attitude that deserve equal attention.

Indeed,

current and near-term future developments augur well for

greatly enhancing this important naval warfare area.

Today’s ASW Legacy

Like many other major issues facing today’s Navy,

our current concerns about ASW trace back to the end of

the Cold War and our subsequent redirection of emphasis

toward potential conflict in the littorals. Our existing

ASW capabilities are largely those that had been so

painstakingly created to prevail over the Soviets in a

global, deep-water conflict, and they are only partially

adequate for the new and different environments we face

today. Shallow water, near-shore oceanographic phenomena,

asymmetric diesel and advanced Air-Independent Propulsion

(AIP) submarine threats, and meager information about the

potential battle space all contribute to significant

uncertainties about our ability to contain the new and

different undersea threat we face now. Further, since the

Russian Navy has continued to build state-of-the-art

nuclear submarines with global reach, the “Cold War”

threat, though numerically smaller, remains to be

countered also.

Yet today, ASW seems to some observers to

be a tennis match with no opponent on the other side of

the net. With the end of the Cold War and the

simultaneous implosion of the Soviet/Russian navy, we are

no longer seriously challenged at sea, except perhaps by

local naval powers intent on acquiring modern submarine

forces or new mine warfare capabilities. Consequently, we

have not been able to practice ASW very realistically.

Also, although our equipment has grown older and less

effective, we have not noticed much impact, because the

challenge has been so minimal. Nevertheless, the Navy’s

ASW proficiency has declined in the last decade, and we

must reassess future requirements and capabilities to

meet an uncertain but still-dangerous threat.

The New ASW Assessment

Under the pressure created by a similar ASW crisis early

in World War II, the Navy regrouped by establishing the

Tenth Fleet to coordinate an integrated response to the

threat. Within three years, the Allies had won the Battle

of the Atlantic. Now, with the recognition that ASW

challenges are steadily increasing world-wide, the Navy

is regrouping again. With “coordination” and

“integration” as key elements, the

Anti-Submarine Warfare Division (N84) in the Office of

the Chief of Naval Operations has been given a central

responsibility for developing a requirements-based ASW

plan, as a direct outgrowth of the Navy’s recent ASW

assessment.

There are three fundamental truths about

ASW. First, it is critically important to our strategies

of sea control, power projection, and direct support to

land campaigns. The Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu

recognized some 2,400 years ago that the best way to

defeat an enemy is to attack his strategy directly. As

the United States looks to refine its focus on forward

presence and power projection from the sea, as envisioned

in the 1994 Forward...From the Sea strategic concepts

paper, the submarine threat that denies, frustrates, or

delays sea-based operations clearly embodies Sun Tzu’s

dictum and attacks our strategy directly.

During the 1982 Falklands conflict, for

example, the Royal Navy established regional maritime

battlespace dominance with a single submarine attack, the

sinking of the Argentine cruiser General Belgrano by the

nuclear attack submarine Conqueror. But the British were

fighting at the end of a perilously thin, 8,000-mile long

logistics lifeline, and themselves were extremely

vulnerable to submarine attack. Had the single Argentine

Type 209 submarine that got underway, San Luis, been

successful in just one or two of its several attacks

— which were stymied as a result of an improperly

maintained fire control system — and sank or

seriously damaged one of the two British small-deck

carriers or several logistics ships, the outcome might

have been very different. We must recognize that in today’s

and tomorrow’s conflict scenarios, the submarine is

an underwater terrorist, an ephemeral threat. It will

force us to devote a great deal of resources and time,

which we might not have.

Second, ASW is a team sport —

requiring a complex mosaic of diverse capabilities in a

highly variable physical environment. No single ASW

platform, system, or weapon will work all the time. We

will need a spectrum of undersea, surface, airborne, and

space-based systems to ensure that we maintain what the

Joint Chiefs of Staff publication Joint Vision 2010 calls

“full-dimensional protection.” The undersea

environment, ranging from the shallows of the littoral to

the vast deeps of the great ocean basins — and polar

regions under ice — demand a multi-disciplinary

approach, subsuming intelligence, oceanography,

surveillance and cueing, multiple sensors and sensor

technologies, coordinated multi-platform operations, and

underwater weapons. Most impor-tantly, it takes highly

skilled and motivated people.

Finally, ASW is hard. The San Luis

operated in the vicinity of the British task force for

more than a month and was a constant concern to Royal

Navy commanders. Despite the deployment of five nuclear

attack submarines, 24-hour per day airborne ASW

operations, and expenditures of precious time, energy,

and ordnance, the British never once detected the

Argentine submarine. The near-shore regional/littoral

operating environment poses a very challenging ASW

problem. We will need enhanced capabilities to root

modern diesel, air-independent, and nuclear submarines

out of the “mud” of noisy, contact-dense

environments typical of the littoral, and be ready as

well to detect, localize, and engage submarines in deep

water and Arctic environments.

Exercises with high-end diesel subs,

such as the South Korean ROKS

Lee Jong Moo (SS-66), shown here with a P-3C and

USS Columbus (SSN-762) during RIMPAC 98,

are vital to improving Fleet ASW proficiency.

The 1997 ASW Assessment gathered inputs

from Fleet operators the intelligence and technical

communities, and the Navy and Joint Staffs. The study

team framed their effort by postulating several likely

future ASW campaign scenarios involving U. S. coalition,

and adversary forces and estimating the outcomes using

both analytical and simulation techniques. Lessons

learned were couched in accordance with the traditional

responsibilities of the Navy Department to “train,

organize, and equip” a navy. Strengths and

weaknesses were identified in each area, with mixed

results. The “good news” is that our equipment

— the platforms, sensors, weapons, and C4I

infrastructure planned for the coming decade — is

quite good. Though much remains of the Cold War,

deepwater legacy, it creates a solid foundation upon

which to build the enhancements needed for effectiveness

in the littoral, and new information processing

technologies will help fill the remaining gap. On the

other hand, today’s ASW training is deficient for

reasons described above, and our command organization for

coordinating multi-platform ASW and supporting it with

Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance assets

ashore could be improved. In seeking to be better

organized, the fact that our present approach is so

platform-oriented is a major stumbling block.

The Way Ahead

Based on the findings of the 1997 assessment, the Navy is

now developing a set of integrated ASW requirements,

designing a mission architecture in response, and

drafting a corresponding investment plan for the

out-years. As the architecture, size of the force, and

capabilities will be requirements-based, the starting

point needs to be our best estimate of the submarine

threat 15 years or so from now. At that time, a likely

regional adversary may well be able to deploy 35-40

modern submarines in a mix of nuclear, diesel, and AIP

types, most equipped with respectably modern sensors and

weapons from the international arms market. In this

light, and in a time of constrained resources, the

overall ASW strategy most appropriate for future

expeditionary warfare may well be some kind of “moving

area control.” This would guarantee local undersea

superiority or time-limited sub-free “havens”

in areas of current interest, rather than the regional,

if not global, superiority we sought during the Cold War.

Thus, by successively concentrating forces and ISR assets

only where needed for Sea Lines of Communication (SLOCs)

or force protection, our forces can be focused optimally

and their limitations at least partially finessed. The

integrated ASW requirements, the mission architecture,

and the long-range investment plan are all currently in

work and will be updated continually to shape the Navy’s

response to the evolving submarine threat.

Regrouping for Success

In retrospect, this period of the late 1990s will be

viewed as a period of retrenching for ASW in the U.S.

Navy. The new challenge is becoming clearer, and it is

time to shift gears. Even though much of the Cold War

threat is gone, the Navy has not failed to appreciate the

future importance of ASW as a contributor to achieving

the visions articulated in Forward...From the Sea and

Joint Vision

2010. Other important policy documents — the Defense

Planning Guidance (DPG) and the Navy’s Long-Range

Planning Objectives — also call for a robust ASW

capability that links warfare requirements to the real

dangers and vulnerabilities introduced by the

proliferation of next-generation submarines. Evidence of

the Navy’s revitalization of ASW is beginning to

accumulate.

For example:

Senior Leaders are

Engaged.

The Chief of Naval Operations has

testified before Congress that submarines and

mines are among the most serious threats to the

U.S. Navy. He chaired a CNO Executive Board (CEB)

on ASW in July 1997. Along with Secretary of the

Navy John Dalton, the CNO signed the 1997 ASW

Assessment, which was forwarded to the Congress

earlier this year. Excerpts from CNO’s more

recent ASW “focus” statement are found

in an accompanying sidebar. Most importantly, the

CNO has led the way in providing stable funding

for ASW accounts ever since he took office.

Following up, Fleet Commanders are revamping ASW

training and experimenting with new technology.

There is a growing awareness by all echelons of

the Navy’s leadership that the cycle of ASW

is on the upswing.

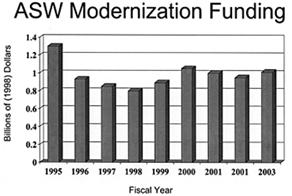

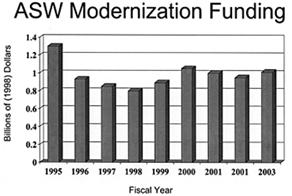

Funding has

stabilized.

Despite the challenge of ensuring

today’s readiness while investing in the

future, current funding projections show that the

Navy is serious about modernizing ASW systems,

sensors, and weapons.

New technology is

continually being developed and fielded.

The Navy is experimenting with

several new acoustic and non-acoustic

technologies especially tailored to the littoral

environment. A few examples include:

Distant Thunder.

This is a new body of advanced signal processing

techniques for shallow water, littoral

environments that uses innovative computer

processing to detect target echoes generated by

low frequency active sources.

Interactive

Machine-Aided Training (IMAT).

This is an exciting new training approach that

uses computer-generated visualizations of

underwater sound fields and propagation phenomena

to develop operator intuition and greater

understanding of sonar conditions and sensor

effectiveness.

Advanced Rapid COTS

Insertion (ARCI).

The submarine community is leading the way in

introducing commercial off-the-shelf (COTS)

computer technology into its ASW systems and

sensors, and processing gains are dramatic. For

example, when all ARCI builds are installed in an

Improved Los Angeles (SSN-688I) attack submarine,

that single SSN will command as much

signal-processing power as the entire non-ARCI

SSN-688 fleet at sea today.

Advanced Deployable

System (ADS). ADS is a rapidly

deployable, short-term undersea surveillance

system designed for ASW monitoring of shallow

water littoral operating areas. It will use an

expendable, battery-powered, large-area field of

passive acoustic arrays, interconnected and

cabled to shore with fiber-optic cables.

Rapid Environmental

Assessment. The Ocean-ographer of

the Navy is developing techniques and procedures

to assess the ASW environment of the littoral

battlespace for rapid optimization of sensors and

weapons and decision support. Remote offboard

sensors and satellite signal processing play key

roles.

Advanced Technology

Demonstrations (ATDs). ASW projects

have fared well in recent years in this important

program that encourages high-risk projects that

offer potential for high payoff.

The Navy is articulating

more focused ASW requirements.

The undersea warfare community is

pioneering a new approach to defining warfare

requirements that uses a “systems integrator”

process. While developing the budget, ASW program

planners now treat the entire architecture as a

whole, recognizing that effective ASW requires a

chain of systems that can only be as strong as

its weakest link. Future budgets will be

determined by an investment strategy that seeks

to strengthen the weak links while exploiting

promising opportunities in training,

organization, and technology.

Prospects for the Near Term

Despite this evidence of recent progress, there remain

several shortfalls that could be addressed by additional

near-term initiatives. Most notably, we are studying the

creation of an ASW “center of expertise” at the

numbered fleet level, which would hold responsibility for

ASW training, the development of multi-platform

coordinated tactics, and experimentation. This

organization could have the power to control real assets

— much as did Tenth Fleet in World War II — and

certify each deploying battle group in integrated ASW

proficiency that includes the exploitation of ISR assets,

such as the Integrated Undersea Surveillance System

(IUSS). We need regular access to an “adversary

squadron” of modern diesel-electric submarines, and

we ought to make maximum use of allied and friendly

navies to fill the need, subsidizing them if necessary.

As a “force-multiplier” for our limited

platform assets, we should be looking at more commonality

of ASW sensors and signal processors, with open, “plug-and-play”

architectures that facilitate flexible applications on a

variety of platforms. Finally, the U. S. Coast Guard’s

“Deepwater” initiative for providing a “system

of systems” for missions beyond 50 miles offshore

— and which will include both a new “Maritime

Security Cutter” and several aircraft types —

may offer significant opportunities for littoral ASW

mission and asset sharing.

Overall, ASW is finally emerging from a

decade of atrophy. Acknowledging and understanding ASW’s

recurring cycles of “boom-and-bust” can

accelerate the awakening that is now underway in the

Navy. We need to avoid any further unraveling that could

permit the kind of devastating blows that history has

shown can be fatal to a national military strategy that

relies so heavily on unimpeded sea lines of

communication. The Battle of the Atlantic in 1942-1943

and the Falklands War of 1982 have shown what is at

stake.

A Rising Tide

ASW embodies the essence of sea control, which in turn

remains the foundation for global power projection. The

Chief of Naval Operations clearly understands the

importance of both: “In fact,” as Admiral

Johnson noted, “at the core of U.S. security

requirements lies one prerequisite — sea control….

If we cannot command the seas and airspace above them, we

cannot project power to command or influence events

ashore; we cannot deter; we cannot shape the security

environment.”

We are awakening to the demands and tasks

ahead. There is renewed interest by the Navy’s

leadership in core ASW competencies. Our intelligence

services and operating forces are, once again, focused on

the new generation of an old and familiar threat. Our

technical community is addressing novel solutions to a

complex, multi-faceted problem. In short, ASW is coming

back. The greatest challenge now will be holding us

“steady as she goes” on the course to recovery.

SURTASS ship USNS Able

(T-AGOS-20)

Captain John Morgan is the Director,

Anti-Submarine Warfare Division (N84), in the Office of

the Chief of Naval Operations. A Surface Warfare Officer

qualified in submarines, he has extensive multi-platform

ASW operational experience.

|