|

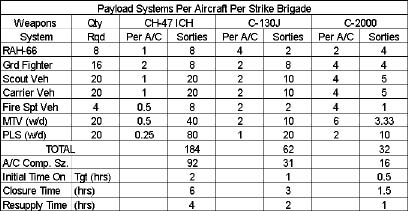

| Comparison of the air-ground strike performance of three aircraft. |

Army XXI is a power projection force delivering to the warfighting commander in chief the dominant maneuver capability called for in Joint Vision 2010. This capability, in turn, depends on agile focused logistics provided by the dynamic distribution-based system that is key to the Revolution in Military Logistics (RML). This article describes the challenge presented by the dominant maneuver of powerful land-power strike forces and their subsequent sustainment through distribution-based, focused logistics. The Army must reach deep, move fast, and sustain on the run, and this demands an efficient, capable, projectable, and maneuverable intermodal distribution system. Aviation is a key component of modern intermodal distribution systems, and the need for advanced intratheater air transport is critical. But the Army faces the risk of experiencing a shortfall in both the quantity and capability of projected air assets for the first two decades of the 21st century.

An Evolution of Thought

As the dust of the Cold War settled, strategic thinkers considered the emerging dynamics of the post-Cold War world. Other futurists were contemplating the significance of the fledgling information age, the new technologies it brought, and the impact it would have on the global society and the global economy. As these two lines of thought converged, it became apparent that a Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA) was underway—a revolution that would transform the way wars are fought and won. Nations and armies that exploited the opportunities presented by the RMA would dominate the battlefields and crises of the next century, but those who ignored the RMA would fail famously. The Army, along with the rest of the Department of Defense, wasted no time in evaluating this promised revolution and began a series of studies and projects that have produced revolutionary new approaches to force design and employment.

The Army After Next (AAN) project produced intriguing and powerful operational concepts that called for self-mobile, air-mechanized battle forces to operate independently for a number of weeks hundreds of miles inside an opponent's territory. The Army logistics community articulated the RML vision to support these battle forces as well as to add economy and efficiency to the projection and support of the more numerous and more conventional forces of the digitized Army XXI.

Operationally, these battle forces performed magnificently in war game after war game. The support concepts appeared to be effective and, for the most part, doable. The only devil was in a few of the technical details. Most troublesome was the inability of high-performance armored vehicles to operate without fuel resupply for weeks at a time. The RML support concepts proposed a dynamic, distribution-based logistics system that could be projected rapidly and operated efficiently to provide the widely distributed battle forces with uninterrupted fuel and ammunition supplies. However, the biggest concern and showstopper was the cost of this high-tech force package.

Strategic thinkers at the Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) and in the Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Research, Development, and Acquisition (SARDA), among others in the futures research community, are beginning to see an interesting opportunity. Much of the AAN battle force dominance can be achieved much sooner by leveraging the technologies and systems we have today or those that soon will emerge from the labs.

The Strike Force Concept

The strike force concept presented by TRADOC and refined by SARDA proposes to use tactical airlift to achieve an early form of dominant maneuver. The current concept is to use existing airlift technologies or those that will soon enter service, such as the C-130J transport. However, there may be great advantages to developing an intratheater airlifter that exploits current and emerging aviation technologies to increase theater airlift capabilities.

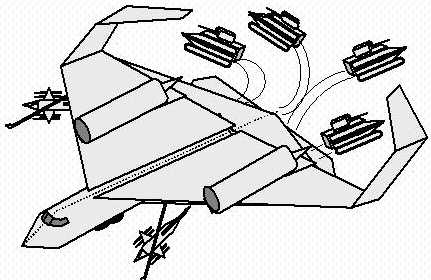

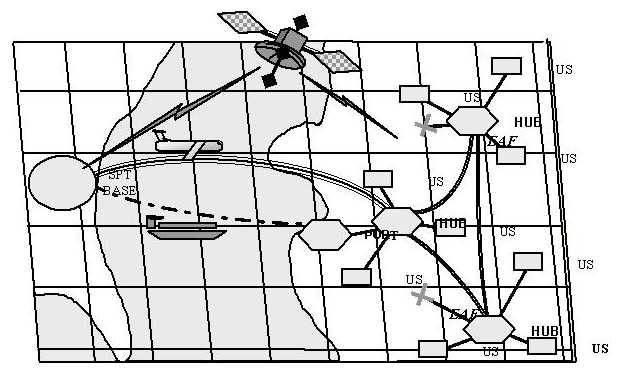

For comparison, imagine a mission that calls for a joint air-ground strike force to seize an airstrip 200 miles from the current friendly position and then calls for the strike force to conduct combat operations to capture or destroy opposing forces within a 50-mile radius of the airstrip. This scenario is representative of the high-end challenges of the early 21st century, combining the "need for speed" seen in Operation Just Cause with a significant armor threat, as seen in Operation Desert Storm. The airstrip is either an existing facility or terrain suitable for unimproved-field landings and takeoffs. The alternative airlift platforms are the C-130J, the CH_47 improved cargo helicopter (ICH), and a hypothetical state-of-the-art airlifter we'll call the C-2000.

Future Airlift Possibilities

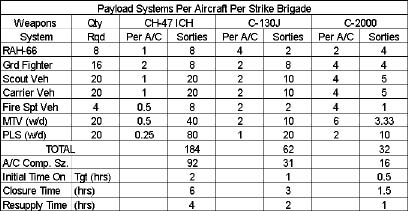

The C-2000, as depicted at right, has several unique features that enhance its tactical airlift capability. It uses a blended wing-body design and a C-wing configuration with overblown wings to further enhance short takeoff performance. The blended wing-body would provide a wider cargo bay to support simultaneous parallel loading and unloading of four 15-ton light armored vehicles. This would allow the four vehicles to roll off the aircraft within a minute of landing. Two RAH-66 Comanche recon-attack helicopters would be carried as under-wing loads on the lead C-2000's. These lead aircraft also would carry a small number of another theorized system—a two-soldier, 10-ton ground fighter, used along with the Comanches to seize and hold the airstrip long enough for the full insertion of the strike force. These teams then would move into a force reconnaissance and security role. Tactical air support fighters and gunship versions of the C-2000 also would support the joint strike force, and together they could initially suppress opposition at the target airstrip and the immediate vicinity.

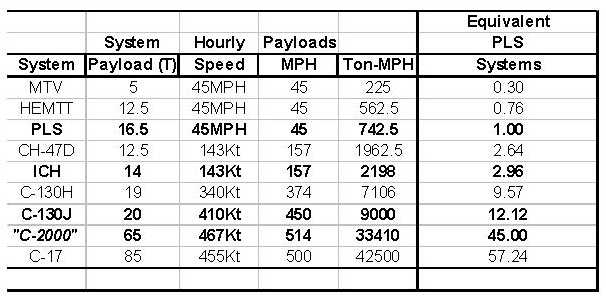

For comparison (see chart below), a C-130J would carry the Comanches internally, which could cause an unacceptable time delay at the target. The Comanches could fly to the objective on their own, but this would require refueling in the target area. They also would complicate strike timing since they are slower than the C-130's. Both of these alternatives incur a possibly unacceptable time delay. In the case of the CH-47 ICH option, Comanches and other helicopters would fly out with CH-47 ICH. They would need to refuel at the objective, which may not be supportable tactically. Comparative air-ground strike force performance of each aircraft option is shown in the table below.

|

| Comparison of the air-ground strike performance of three aircraft. |

To complete the scenario, the lead C-2000 airlifters would carry two Comanches under the wing along with four ground fighter vehicles. This leaves some unused lift capacity that could enhance slightly the performance of the lead assault aircraft, or it could be used to haul needed weapons or sustainment supplies. Once the Comanches and the ground fighters dominated approximately a 10-kilometer radius of land around the airstrip, the airlifters would rapidly insert the rest of the strike force. The concept would call for 16 aircraft to fly out en masse and insert the entire strike force in close to 30 minutes for a 200-mile dominant maneuver.

|

C-2000 next generation intratheater airlifter. |

Additionally, the ICH helicopters would not be able to carry the palletized loading system (PLS) trucks of the support force. The PLS sorties shown in the chart are based instead on an equivalent lift capability provided by additional 5-ton medium tactical vehicle trucks. As shown, the ICH's would carry the Comanches to the objective area, thus conserving fuel for the attack helicopters. If the Comanches self-deployed, eight fewer ICH sorties would be required. Even so, it is clear that this 200-mile strike mission should not be conducted using ICH lift.

The greater speed and carrying capacity and the reduced unloading times proposed for the C-2000 allow it to close the strike force in half the time of a C-130J-equipped force. The limited items that the ICH could deliver take three times as long to close in the battle area. Time-on-target and closure time estimates shown on the chart are based on air speed and loading and unloading time of aircraft. The blended wing-body postulated for the C-2000 allows simultaneous loading or unloading of at least three vehicles, and assumes loading and unloading speed is part of C-2000 design. This shortens loading and unloading time to less than 10 minutes versus the 30 minutes assumed for the C-130J.

Resupply times are based on the time required for aircraft to reload selected support vehicles; fly back to the staging area; unload, resupply, and reload support vehicles; and fly back to the area of operations. Alternatively, aircraft can return empty, load cargo, and return to the area of operations and transfer cargo to support vehicles. This provides a two-lift sustainable strike capability, with combat forces coming in on the first lift and tactical support forces coming in shortly behind the combat forces. The time estimate for either option remains roughly the same and would depend on the scenario.

|

| Joint RMA strike force using advanced intratheater airlift. |

Flying the support vehicles back would reduce the sustainment payload for the return trip; however, the dedicated airlift fleet sizes still would support this option, which might enhance force security between refuel-rearm cycles or help the support vehicles to keep pace with the fast-moving strike force. The primary inefficiency is higher aircraft fuel use, since the aircraft fleet size is based on tactical needs to close the strike force quickly. Note that a three-lift strike concept also could be an option. The first wave would seize and hold the airstrip, the second wave would deliver the rest of the combat force, and the third wave would deliver the support force loaded with initial sustainment. The C-2000 could exploit this option with approximately 10 aircraft, deliver the same initial time-on-target, experience the same combat force closure times, and accomplish total force closure within 1.5 hours.

|

| Focused distribution-based logistics...an agile dynamic distribution network. |

Operating tactical airlifters and light armored vehicles in the near vicinity of heavy opposing armored forces will require some doctrinal adjustments. One key to the strike force concept is that technology soon will support advanced hit avoidance for vehicles, which effectively provides virtual armor to these lighter vehicles as well as to the aircraft. Additionally, state-of-the-art weapons technology soon will provide precision, over-the-horizon, direct fire weapons and missiles. Finally, the strike force commander will have to fight in a manner that exploits the decisive overmatch of his weapon systems but avoids losing that advantage in close-combat attrition fire fights with the heavier opposing armored forces.

|

| A theater intermodel distribution network. |

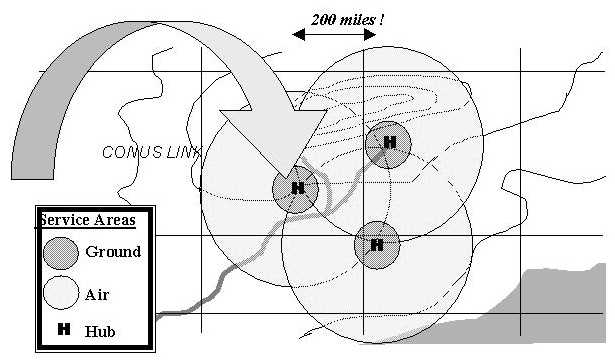

Strike Force Sustainment

The second key enabler of the strike force concept is the sustainment of the strike forces during a significant, high-OPTEMPO operation, likely lasting several days. A key concept of the RML comes into play here. The RML calls for a dynamic, projectable, and maneuverable, distribution-based logistics system. This will allow the theater support command to reach out to the strike forces and provide uncurtailed sustainment. This is one example of how the RML will empower commanders with logistics. The figure above depicts the global reach of RML distribution-based logistics, and the figure below shows the tactical side of the distribution-based logistics network in reaching out to support a joint strike force operation.

|

| Ground and air distribution platforms. |

The speed and long-haul capacity of an intermodal distribution system are clearly superior to those of a pure truck distribution fleet. However, within a local radius of about 50 miles in a tactical environment, direct delivery by aircraft is neither practical nor efficient. That is why RML distribution-based logistics stresses the need for an integrated, intermodal, air-ground distribution system. The chart at left compares ground and air distribution platforms, using a common metric of ton-miles per hour. Once again, though, it is easy to see that something more capable than a C-130J will be required to implement these new RML support concepts. In fact, the cargo moving advantages of the C-130, even of the most modern J model, do not appear to be much more attractive than using a larger truck fleet. The 12-to-1 tradeoff of PLS trucks offered by the C-130J hardly justifies the added cost of the aircraft. However, a new medium airlifter with the speed and capacity of the hypothetical C-2000, offering a 45-to-1 offset of PLS trucks and a greater delivery speed for crucial cargo, makes an RML intermodal distribution system an attractive and powerful enabler of RMA-style warfare.

WebsitesThe following websites provide more information on intratheater airlift:http://www-tradoc.army.mil/dcsdoc/aan.htm(Deputy Chief of Staff for Doctrine, Army Training and Doctrine Command, Army After Next Insights: Beyond Knowledge and Speed, 1998 briefing)http://aero.stanford.edu/reports/nonplanarwings /Configuration.html(Kroo, Ilan, C-Wing Configuration Development)http://lmasc.com/c-130j/technical.htm(Lockheed Martin Aeronautical Systems Company, C-130J Hercules Specs & Performance)http://www.tacom.army.mil/dsa/pm_htv/(Program Manager Heavy Tactical Vehicles)http://www.tacom.army.mil/dsa/pm_mtv/(Program Manager Medium Tactical Vehicles)http://www.boeing.com/rotorcraft/military/ch47d /ch47dspec.htm(The Boeing Company, CH-47D Specifications)http://www.hqmc.usmc.mil/factfile.nsf /7e931335d515626a8525628100676e0c/0992276ba1b2f2b68525626e00494022?OpenDocument(United States Marine Corps Fact File, KC-130 Hercules) |

The capabilities assumed for the C-2000 are based on the actual specifications of the Boeing YC-14 medium airlifter prototype. This technology demonstrator was flown in the late 1970's. So the actual C-2000, which incorporates 20 more years of aeronautical engineering advancement, could provide even greater benefits for RML distribution-based logistics and the sustainment of globally projected Army forces. As Boeing proved in its recent 777 program, modern engineering, leveraging simulation, computer-assisted design and computer-assisted manufacturing (CAD-CAM), advanced flexible manufacturing, and optimized supply chains can cut aircraft design and production time by more than half. So the opportunity is there if the United States chooses to acquire such an advanced intratheater airlifter and, with it, the power of dominant maneuver and focused logistics. ALOG

Mark J. O'Konski is Director of the Army Logistics Integration Agency in the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics, Department of the Army.

David Payne is a principal research analyst for the Logistics Future Research Group with Innovative Logistics Techniques, Incorporated (INNOLOG), McLean, Virginia.